August 24, 2009

August 24, 2009

Mammography and the Patient Information Form

By Leonard Berlin, MD, FACR, and Marc J. Homer, MD, FACR

Radiology Today

Vol. 10 No. 15 P. 22

Editor’s Note: Leonard Berlin, MD, FACR, is a professor of radiology at Rush University Medical College and the chairman of the department of radiology at Rush North Shore Medical Center in Skokie, Ill. He began writing on risk management and malpractice issues in a series of articles in the American Journal of Roentgenology. Those articles became the basis for his well-known book Malpractice Issues in Radiology. The third edition is available from the American Roentgen Ray Society (www.arrs.org).

Marc J. Homer, MD, FACR, is a professor of radiology at Tufts University School of Medicine and the chief of the mammography section at Tufts Medical Center.

The Case

A 42-year-old woman consulted her family physician because she thought she felt a lump in her left breast. The physician examined the woman’s breasts but was uncertain as to whether a definite mass was present. He suggested that the woman undergo mammography and with her permission asked his office secretary to make an appointment in the radiology department at a nearby hospital for the study. Before the patient left the physician’s office, she was told that she was scheduled for a mammogram in 3 days and that she should bring any previous mammograms with her when she appeared for the appointment. The woman responded that she had never before undergone mammography.

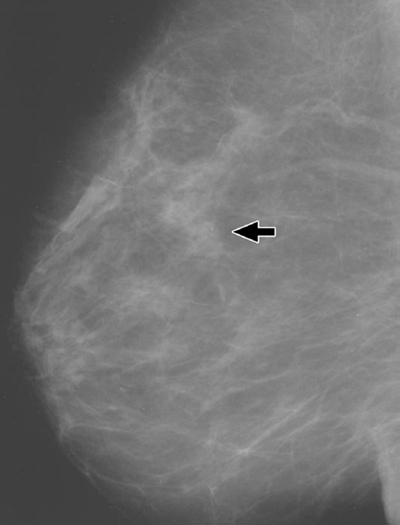

The patient kept her appointment, the mammographic examination was carried out, and it was interpreted by the radiologist as showing no evidence of malignancy (Fig. 1A). The final assessment category was negative for malignancy. After receiving the written mammographic report, the family physician telephoned the patient to inform her of the results and instructed the patient to schedule an appointment for a return visit to his office in 3 months for a follow-up breast examination. He also told her to return immediately if she noticed any change in the breast or developed a definite lump.

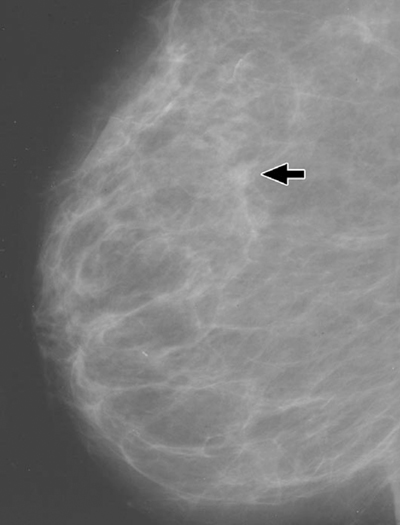

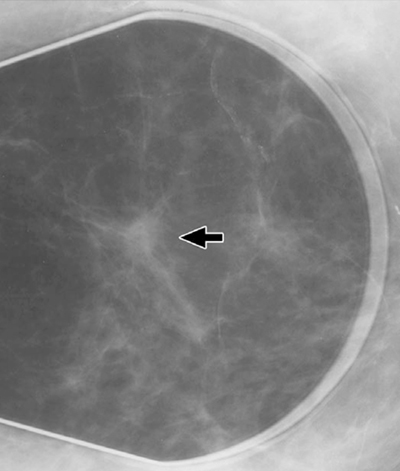

The patient did not return to the physician until 1 year later, at which time a definite mass in the left breast was present. The physician ordered another mammographic examination, and on this occasion the radiologist reported an 8-mm noncalcified mass with indistinct margins in the 12-o’clock position of the left breast (Fig. 1B). A spot radiograph revealed spiculation (Fig. 1C). The final assessment was highly suggestive of malignancy. A biopsy sample obtained the next day revealed infiltrating ductal carcinoma. At surgery, three of 15 lymph nodes were involved with tumor. The patient elected to have breast conservation therapy and received chemotherapy and radiation treatments.

Six months after the diagnosis of breast carcinoma was established, the patient filed a malpractice lawsuit against the family physician and the radiologist, alleging that the 1-year delay in the diagnosis of her breast cancer dramatically reduced her chance of survival.

Malpractice Issues

The attorney for the plaintiff retained two expert witnesses, a family practitioner and a radiologist. The expert in family practice reviewed the defendant family physician’s medical records and found that although the family physician claimed he had told the patient to come back in 3 months after the initial mammogram had been interpreted as showing normal findings, his written office notes stated only, “Patient informed of mammogram results.” The plaintiff’s expert also noted that the patient alleged in a signed statement that she was never told to return to the family physician for reexamination. The patient further claimed that she returned to the physician 1 year later on her own because she felt a definite change in her breast while performing a self-examination.

The radiology expert retained by the plaintiff focused on the fact that although the woman presented for evaluation of a left breast lump, a screening mammogram consisting only of a mediolateral oblique view and a craniocaudal view of each breast was obtained, and the defendant radiologist dictated a negative screening report without any reference to the patient’s complaint of the breast lump. The plaintiff’s expert maintained that a diagnostic examination with additional views should have been performed, and the radiology report should have specifically addressed the patient’s complaint. The radiology expert also asserted that there was a vague density on the original mammograms at the site of the eventual breast cancer, evident only on the mediolateral oblique view (Fig. 1A), and that if a compression view had been obtained, more likely than not a mass would have been revealed. At that point, concluded the plaintiff’s radiology expert, additional views would have been obtained in an orthogonal projection and a mass with indistinct margins would have been identified, leading to immediate biopsy.

The attorney appointed by the malpractice insurance company to represent the defendant radiologist retained a radiology expert to evaluate the mammograms and medical records. In his review of the mammographic study, the expert noted on the mediolateral oblique view a vague density in the central part of the left breast but did not consider it to be a significant abnormality, inasmuch as it had a similar appearance to other islands of scattered fibroglandular tissue present in both breasts. The density was isodense compared with other areas of fibroglandular tissue, contained no microcalcifications, and even appeared to have fat interspersed within it. Although it was clear that this was the area in which the spiculated breast cancer appeared 1 year later, even in retrospect, the expert believed that there was no reason to be concerned about this density and that it was not a breach of the standard of care to ignore it.

The radiology expert reported his opinions to the defense attorney and requested that the attorney send him the patient questionnaire for review. The attorney was unaware of this document because it was not contained in the hospital medical records. The expert explained to the attorney that before beginning a mammographic examination, it is customary—in fact, mandatory—to obtain from the patient an information form containing specific information, such as the indication for mammography, risk factors, and the site of any previous breast surgery. This form is reviewed by the radiologist before interpretation of the mammograms, added the expert, who then suggested that the attorney speak to his client in an attempt to locate the patient information form.

Five days later, the patient information form was found and sent to the radiology expert for review. The form was filled out by the patient herself before the mammograms had been obtained. Her written answer to the question, “Why are you having this examination?” was “routine.” Based on this answer, the expert concluded that despite the plaintiff’s allegation that the radiologist knew the patient was there for evaluation of a left breast lump, there was no evidence to support this contention. Furthermore, the requisition that had been sent from the family physician’s office to the hospital was marked “screening.” The radiology expert concluded that neither the technologist nor the radiologist had any knowledge that the patient had a left breast lump and were therefore justified in viewing the mammography as screening. In a discovery deposition conducted 1 month later, the radiology expert for the defense repeated his opinions that it was perfectly reasonable for the radiologist and his staff to believe that the mammography was a screening examination to be carried out on an asymptomatic patient, the standard views obtained were appropriate, and the mammographic interpretation was appropriate.

The attorney for the defendant family physician recognized that without any documentation in the office notes that the woman was told to return in 3 months for a repeated physical examination of the breast, it would be difficult to convince a jury that the physician’s recollections were correct and that the patient’s were not.

The defense attorney added that even though he would be able to provide testimony from an expert oncologist that the 1-year delay did not appreciably decrease the patient’s survival, the attorney for the plaintiff would undoubtedly produce an oncology expert who would render a contradictory opinion. The defense attorney therefore recommended that the lawsuit be settled.

With the agreement of the defendant family physician, the parties commenced negotiation and eventually agreed to a settlement of $500,000, all of which was attributed to the family physician. The radiologist was dropped from the lawsuit.

Discussion

The plaintiff’s case was based on three allegations: a mammographic finding on the mediolateral oblique radiograph was missed; a diagnostic rather than a screening mammogram should have been obtained; and as part of a diagnostic mammogram, additional views highlighting the area in which the lump was palpable should have been done.

The expert radiology witnesses for both the plaintiff and the defense agreed that a density was present on the mediolateral oblique view of the left breast, but because they differed as to whether the density should have been interpreted as potentially abnormal, the attorney for the plaintiff recognized that simply to argue before a jury that the lesion was missed might not be very persuasive. It was clear to the plaintiff’s attorney that the key to the case would be to argue that additional views were required and should have been obtained because a diagnostic mammogram was indicated for any woman who has said that she felt a lump in her breast.

There are three pathways by which a mammogram can be designated diagnostic rather than screening. These include history from the referring physician, history from the patient, or the conversion of a screening mammogram into a diagnostic mammogram by the radiologist because of the presence of abnormal radiographic findings. The radiologist can act only if accurate information is received from any or all of these three sources. Here, the history from the referring physician’s office was clearly incorrect in that a screening mammogram had been requested. As to the history given by the patient, the evidence was conflicting. The plaintiff’s attorney disclosed a written statement of the patient in which she insisted that she told the technologist she was undergoing mammography because of a palpable lump in her breast, but the radiology expert for the defense provided critical advice in this case by educating the defense attorney about the patient information form. It was this form that ultimately provided incontrovertible evidence that the patient did not inform anyone she was undergoing mammography for the evaluation of a breast lump.

Information regarding a patient’s history and clinical findings is the pivotal issue on which the determination of whether a mammographic examination is to be screening or diagnostic is made. Obviously, screening mammography is appropriate to detect unsuspected breast cancer in asymptomatic women1, whereas diagnostic mammography is appropriate to provide specific analytic evaluation of patients with clinically detected or screening-detected abnormalities.2 The means by which patient information should be transmitted to the mammography facility is not formally spelled out in any of the standards published by the American College of Radiology (ACR) or the scientific literature. The ACR Standard for the Performance of Diagnostic Mammography2 addresses the issue only in nonspecific terms:

A statement of clinical concern(s) or indication(s) should be obtained at the time patients are scheduled for diagnostic mammography.

An article published in 2000 was a little more specific3:

Every effort must be made to triage diagnostic from screening patients. This should be done repeatedly, when they telephone for their appointment, when they arrive at the reception desk, and finally by the technologist before the examination begins. This ensures that any clinical problem is brought to the attention of the radiologist.

A previous article addressing the subject of screening and diagnostic mammography was more specific4:

Written communication, either in the form of a requisition filled out by or at least at the behest of the referring physician, or a questionnaire filled out by the patient, is standard practice throughout the country.

In some radiology practices, patients are requested to fill out a preprinted form or questionnaire that contains an unambiguous question asking the patient the reason she is undergoing mammography. The technologist reviews this questionnaire before performing the mammographic examination to determine whether it is screening or diagnostic.

In other practices, it is the technologist who questions the patient and completes the form or questionnaire. This approach is acceptable and may even be more efficient than having the patient fill out the questionnaire, but it could lead to a potential problem. For example, consider the following scenario: A woman presents for evaluation of a breast lump but screening rather than diagnostic mammography is performed. A carcinoma is missed and later a malpractice lawsuit is filed. At trial, the woman insists that she told the technologist in the radiology facility that she was undergoing mammography because she felt a lump in her breast. The patient information form, however, filled out by the technologist while questioning the patient, indicated that the reason for the mammography was routine. Therefore, a screening examination was performed. However, the woman states that she never saw the form before, and whoever filled it out was incorrect. The patient is adamant that the only reason for which she underwent mammography was to evaluate a lump she felt in her breast, and the technologist is equally adamant that the patient told her the mammography was routine. A courtroom situation is now created in which there is finger-pointing between the patient and the technologist, and it will be up to a jury to decide whose recollection of events is the accurate one. Juries may be more sympathetic to the patient’s version of events.

No matter who actually fills out the information form or questionnaire—patient or technologist—radiologists clearly have the duty of acquainting themselves with pertinent clinical information concerning patients whose mammograms they will be interpreting. Indeed, it is the general consensus of both the legal and radiology communities that radiologists breach the standard of radiologic care if, because they fail to apprise themselves of whether patients have expressed or shown any of the indications that would mandate obtaining a diagnostic rather than a screening mammogram, a malignancy is overlooked.4

It is true, of course, that even if the radiologist errs by approving a screening mammogram when a diagnostic one was indicated, the referring physician still has the opportunity of rectifying the situation by reading the mammography report and realizing that the patient has a symptom or sign that was not properly addressed radiologically. In such a scenario, although the referring physician might well be negligent, the physician’s negligence will not relieve the radiologist of his or her initial act of wrongdoing (Strother v Hutchinson, 1981, Ohio; Reed v Weber, 1992, Ohio):

Where an original act is negligent and in a natural and continuous sequence produces an injury that would not have taken place without the act, proximate cause is established, and the fact that some other intervening act contributes to the original act to cause injury does not relieve the initial offender from liability…

There may be more than one proximate cause of any injury. When a defendant’s conduct is negligent and the plaintiff’s injury is the natural and probable consequence of that conduct, the fact that the negligence of others unites with the negligence of the defendant to cause injury does not relieve the defendant of liability.

One additional point should be emphasized. The radiology expert for the plaintiff in the case described in this article asserted that additional views must be obtained whenever diagnostic mammography is undertaken. This opinion is not supported by any ACR standard. Indeed, the ACR Standard for the Performance of Diagnostic Mammography3 states that “diagnostic mammography should be performed under the direct supervision of an interpreting physician … and additional separate studies … may be indicated.”

Summary and Risk Management

The appropriate type of mammographic examination requires that the radiologist understand the indication for the examination. A diagnostic mammogram focuses on a specific problem made known to the radiologist either by history from the referring clinician or the patient, or by the abnormal mammographic findings.

A written form on which the patient has provided pertinent clinical information is the most reliable source from which determination of whether a mammogram is designated as screening or diagnostic can be made.

Risk management in radiology can lessen the likelihood of incurring a medical malpractice lawsuit; maximize the chance of a successful defense if such a suit is filed; and at the same time, enhance the quality of patient care. The following risk management pointers will help radiologists meet all of these objectives when dealing with the role played by information forms in the process of determining whether mammography should be screening or diagnostic.

• Radiologists should have a system in place that ensures that every patient presenting for mammography provides the radiologist with information regarding the patient’s medical history, possible symptoms, and clinical signs.

The patient information form should contain a direct question addressing the patient’s understanding of why the mammogram is being obtained.

The radiology technologist should review the patient questionnaire before obtaining the mammogram to ensure that all questions have appropriate responses. These responses may be the first and only indication that a mammogram should be designated as diagnostic rather than screening. If a patient’s response is absent or ambiguous, the technologist should either clarify the issue with the patient or consult the radiologist for guidance. The identity of the technologist responsible for review of the questionnaire should be clearly indicated on the questionnaire.

• Although it is acceptable practice for the mammography technologist to complete the information form, there may be less chance for misunderstanding if the patient herself fills out the form. In those practices in which the technologist fills out the form, the patient can be asked to affix her signature to it to indicate that she has read and approved the content and all the responses.

Inasmuch as patients often undergo multiple mammographic examinations at the same facility, every patient information form should be appropriately identified with the patient’s name and date so that the form can be matched with the respective mammogram obtained at the time.

Notwithstanding various obligations imposed on the patient and the technologist to supply and authenticate clinical information, radiologists must keep in mind that it is ultimately their responsibility to apprise themselves of all pertinent clinical information relevant to the patient before rendering an interpretation of a mammogram.

— This article appeared in its original form in the American Journal of Roentgenology. It is reprinted here with permission of the American Roentgen Ray Society.

1A

1B

1C

References

1. American College of Radiology. ACR standard for the performance of screening mammography. In: Standards, 2000-2001. Reston, Va.: American College of Radiology; 2000:39-46.

2. American College of Radiology. ACR standard for the performance of diagnostic mammography. In: Standards, 2000-2001. Reston, Va.: American College of Radiology; 2000:47-50.

3. Feig SA. Economic challenges in breast imaging. A survivor’s guide to success. Radiol Clin North Am. 2000;38(4):843-852.

4. Berlin L. Screening versus diagnostic mammography. Am J Roentgenol. 1999;173(1):3-7.