On the Case

On the Case

By John DeBevits, MD; Allan Zhang, DO; and Alex Merkulov, MD

Radiology Today

Vol. 20 No. 1 P. 30

History

A 35-year-old man presented to the emergency department with chronic lower abdominal pain. He also reported increasing trouble urinating, frequently needing to strain to empty his bladder, and feelings of incomplete bladder emptying. He described sporadic burning at the tip of his penis at times. He had been told previously by a provider that his prostate was enlarged. His physical exam was significant for moderate abdominal distension in the suprapubic region with tenderness in the area. Laboratory analysis was significant for minimally elevated creatinine of 1.3 mg/dL. His urinalysis was negative. CT of the abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast was ordered to evaluate his abdominal pain.

Findings

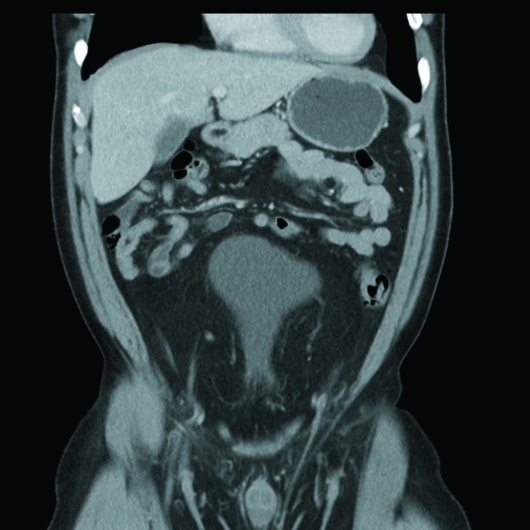

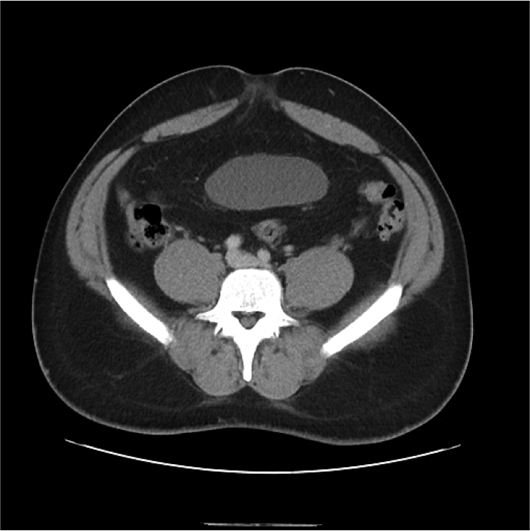

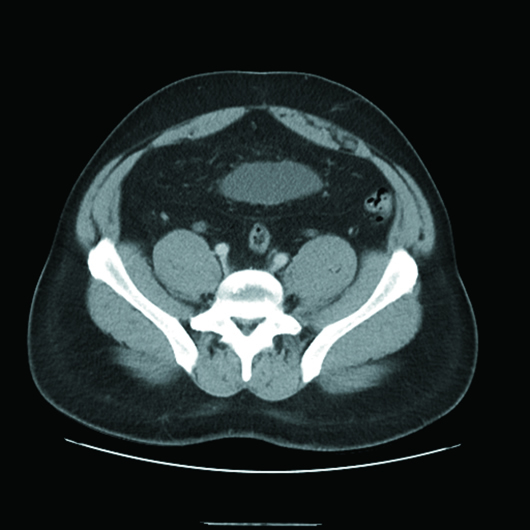

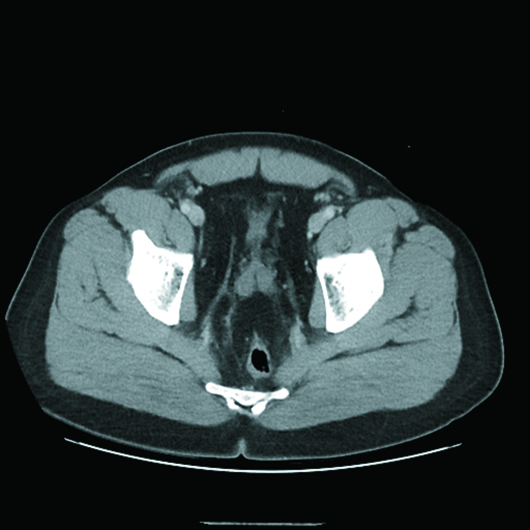

Cross-sectional axial and coronal CT post-IV contrast images revealed an "inverted" pear-shaped urinary bladder, whose normal ovoid shape was extrinsically compressed by extensive hypodense fatty infiltration of the pelvis and lower abdomen. The urinary bladder was in high position with the dome rising to the L3–L4 level (Figures 1, 2, and 3). Also noted was posteromedial displacement of the seminal vesicles (Figure 4).

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

Diagnosis

Pelvic lipomatosis.

Discussion

Pelvic lipomatosis is a rare disorder of increased fat tissue deposition within the spaces of the pelvis, causing extrinsic compression of the bladder, rectum, and blood vessels.

The cause of this abnormal fat proliferation is unknown. It has been hypothesized that the abnormal fat accumulates as a response to chronic urinary tract infection. In cases that have gone on to cystoscopy and biopsy, there was often evidence of proliferative bladder mucosal changes including cystitis glandularis and cystitis cystica, although it is thought that these changes could also be related to chronic lymphatic obstruction due to the fat itself rather than chronic infection.

Other proposed etiologies include endocrine dysfunction, genetic predisposition, and obesity.1-4

Men are overwhelmingly affected compared with their female counterparts, with a male-to-female ratio reported as high as 18:1. There is also a higher incidence within the black demographic.3

Approximately one-half of patients with symptomatic pelvic lipomatosis present with lower urinary symptoms, such as increased frequency, dysuria, nocturia, and hesitancy. Increased frequency and dysuria, which are the most common symptoms, are often long-standing prior to presentation. A suprapubic mass or fullness is reported in up to 83% of patients.3 Nonspecific gastrointestinal symptoms, including constipation, nausea, and vomiting, may coexist. Lower extremity edema attributable to vascular compression is also infrequently reported.

On plain radiograph, pelvic lipomatosis appears as hyperlucent soft tissue mass within the pelvis. Intravenous pyelogram and voiding cystourethrogram show a bladder that is superiorly displaced and demonstrates an elongated neck. The ureters have a normal insertion but are typically medially displaced. The posterior urethra is elongated. The urinary trigone will be elevated though notably without a posterior indentation of an enlarged prostate. The bladder in these cases has been given many descriptors, such as banana-, pear-, gourd-, or tear-shaped.1-4 Mild to severe ureteral obstruction can be seen in 17% to 45% of cases.4 Barium enema evaluation may show an elongated and straightened rectosigmoid colon, the so-called "tower rectum."

CT typically confirms the diagnosis by demonstrating a homogenous, unencapsulated low attenuation (fat density) mass within the pelvis displacing the bladder anteriorly and superiorly with resultant elongation of the bladder neck, giving it the characteristic pear shape. CT is also able to demonstrate a posterior displacement of the seminal vesicles from the posterior wall of the bladder. The rectosigmoid colon will be elongated and straightened similar to findings on barium enema.3

Ultrasound may play a role in diagnosis, particularly 3D sonography, which can show the abnormal morphology of the bladder similar to CT and is useful in evaluating for ureteral obstruction and hydronephrosis. Additionally, displaced position of the bladder can be easily assessed.

Treatment strategies, including antibiotic therapy, steroid use, and/or dietary control, all have demonstrated poor results. Radiation therapy is not only unsuccessful in treating pelvic lipomatosis, but can also result in bladder outlet and rectal strictures.2 Urinary diversion procedures consisting of ileal conduit, nephrostomy tube, or vesicostomy may be required in cases of severe outlet obstruction.

— John DeBevits, MD, is a radiology resident at UConn Health.

— Allan Zhang, DO, is a radiology resident at UConn Health.

— Alex Merkulov, MD, is an associate professor of radiology at UConn Health.

References

1. Engels EP. Sigmoid colon and urinary bladder in high fixation: roentgen changes simulating pelvic tumor. Radiology. 1959;72(3):419-422 passim.

2. Fogg LB, Smyth JW. Pelvic lipomatosis: a condition simulating pelvic neoplasm. Radiology. 1968;90(3):558-564.

3. Heyns CF. Pelvic lipomatosis: a review of its diagnosis and management. J Urol. 1991;146(2):267-273.

4. Klein FA, Smith MJ, Kasenetz I. Pelvic lipomatosis: 35-year experience. J Urol. 1988;139(5):998-1001.