Hospital Employment — Can It Work for Radiologists?

By Timothy W. Boden, CMPE

Radiology Today

Vol. 13 No. 3 P. 18

It’s starting to happen more often. Experts share tips on how to make it work.

Hospitals across the country are buying up medical practices at a pace unseen since the late 1990s. But many of those old deals fell apart within a few years because many hospitals didn’t fully understand the differences between running a hospital system and running a physician practice. Inflated purchase prices and unrealistic salary guarantees for physicians proved economically disastrous for hospitals in many cases. Differences between the unique cultures typical of professional associations and traditional corporations left leaders baffled on both sides of the arrangement.

Unwinding those deals proved costly—not only monetarily but also in terms of goodwill. Recalling the hard lessons learned in the 1990s’ acquisition frenzy, hospitals are trying to make more realistic offers designed to address physician concerns without sacrificing their own profit margin. A more measured approach to managing expectations and aligning hospital and physician incentives seems to be yielding more sustainable employment arrangements.

But how does that work in radiology? Conventional wisdom throughout the radiology community maintains a strong skepticism about hospital employment. But some radiologists are also drawn to the security and stability larger organizations can offer, and they seek relief from the administrative burdens of running a medical practice. So why is it so difficult to create a satisfactory employment arrangement for radiologists and the hospitals with which they have historically been joined at the hip?

The problem isn’t simply hospital employment, according to Timothy Stampp, MBA, chief of corporate development at New York-based consulting group Medical Imaging Specialists (MIS). Stampp, who estimates that at least one-half of MIS’ clients are radiology groups, says strained or failed relationships result when the hospital and the radiology group don’t take into consideration each other’s specific concerns when they first design the relationship structure.

Traditional service contracts between radiologists and hospitals break down in today’s economic conditions—namely, downward pressure on both reimbursement and utilization of high-end imaging studies along with ever-increasing costs. In that environment, traditional agreements don’t form a collaborative relationship, and current trends point to a worsening scenario in the future. Radiologists and hospitals each operate as if they do not care about the issues and concerns faced by the other, which can lead to resentment, hostility, and the relationship spiraling downward (see Figure 1).

Then Is Not Now

Arun Jethani, MA, MIS’ CEO, points out that such simple service contracts, wherein a radiology group agrees to read and report on exams performed in a hospital’s facilities and do its own billing for the professional components, worked just fine 20 years ago. But he notes that several trends in the industry brought new pressures, including the following, not accounted for in those contracts:

- Medicare, Medicaid, and managed care payers shifted hospital reimbursement from fee-for-service to prospective payments based on diagnoses and inpatient days.

- Medicare, Medicaid, and managed care payers retained fee-for-service payment schemes for radiologists but started reducing the amounts paid.

The hospital could no longer collect technical component fees for inpatient imaging, so that part of the service line moved from the revenue column to the expense column. The hospital needed to minimize imaging to control costs. Radiologists, on the other hand, needed to respond to lower reimbursement by maximizing the number of images they read.

- Enterprising radiologists recognized that outpatient imaging could provide new sources of revenue—if they owned their own facilities and equipment. Independent imaging centers began to crop up across the country. Many of these centers decimated hospital-owned outpatient volumes and drew better-paying contracts away from hospitals.

- Hospital payer mixes quickly reflected a much larger proportion of Medicare, Medicaid, and indigent patients, further reducing their per-patient revenue.

Radiologists likewise received lower reimbursement from these payers for their inpatient reads. They began to take a hard line with the hospital: “If you want us not to switch to the competing hospital down the street or build our own center, you will have to subsidize our income.” Hospitals found ways to prop up radiologists’ sagging incomes with payments for services such as medical directorships.

- Developing technology brought “affordable” imaging to other specialists’ practices such as orthopedics, cardiology, and pain management. It also introduced workable teleradiology, allowing radiologists to provide interpretations from any location. That capability expands a radiology group’s potential competitors to more than just nearby groups and gives hospitals more options than just the local groups.

Increased Competition

These developments brought increased competition for everyone. Radiologists and hospitals alike competed with other specialists for outpatient imaging dollars, while the local radiology group could now find itself facing competitors from far outside its local community.

The traditional model may not meet the needs of either the hospital or the radiology group—not even with subsidies or exclusive arrangements. Deteriorating relationships have, in many instances, created adversarial interactions and a loss of trust.

With the Deficit Reduction Act of 2005 (DRA) bringing heavy cuts to outpatient technical component revenue, operating independent imaging centers lost its luster for many radiologists. In fact, some imaging centers find it all but impossible to turn a profit these days. Large lease and loan commitments based on rosy projections that didn’t accurately predict today’s reimbursement levels threaten to turn practices upside down, with practices effectively owing more on equipment and buildings than they are worth or can recoup.

Healthcare reform marched onto the scene in 2010, waving its banner of integration and calling for accountable care organizations. While no one can reliably predict where it will end up, the forces have already been set in motion for a push for greater integration. In the foreseeable future, however, the success of radiologist-hospital arrangements will increasingly depend on tighter—not looser—working relationships.

Whether a hospital-radiologist contract takes the form of full employment or an independent-contractor agreement, the challenges for both parties are essentially the same. The outcome depends on the mechanics of the relationship reflecting each party’s willingness to explore, understand, and address the disparate issues faced by the other. Hospitals and their radiologists must come to an understanding that they are not adversaries but that they are in the same boat paddling in the same direction.

Stampp warns that the future of radiology as a specialty faces greater risk than some of its physicians realize. The increased competition from teleradiologists, management organizations, and other specialists doing their own imaging and interventional procedures threatens to commoditize radiologist services—with contracts simply going to the lowest bidder. Radiologists who refuse to engage themselves in the care integration movement may risk being left out, relegated to a role little more than being highly educated technicians.

Everyone has a vested interest in finding the win-win solution that will satisfy the needs of both hospitals and radiologists. If either side sees the arrangement as unacceptable, there’s a great risk that care will be adversely affected. The trick is to find the “sweet spot” that keeps inpatient utilization and hospital expense under control yet provides the revenue to meet work and income expectations for the physicians. The arrangement must also address outpatient imaging issues, including physician-owned centers that may compete with the hospital.

Seeking the Sweet Spot

Hospitals and radiologists will sometimes bring in outside consultants such as MIS to help them arrive at a workable, win-win solution. Jethani and Stampp, describe some of the steps involved in discovering the unique sweet spot for each situation. Jethani notes there is no magic-bullet formula that works for all groups. Each community requires its own recipe for success. Nevertheless, they usually require certain components of the process, such as the following:

- Explore the real issues and concerns perceived by each party. Stampp refers to this as “the elephant in the room”—the big issues that no one wants to address. When MIS works with a hospital and a radiology group, it starts by surveying individuals and groups on both sides of the table to ascertain and prioritize each one’s needs and demands.

Typical concerns for individual radiologists include salary, retirement benefits, time off, clinical specialization, productivity demands, fairness, and accountability. These issues obviously require different strategies in an employment arrangement as opposed to an independent contractor deal. But they remain among the top concerns in radiologists’ minds.

On the other side, hospitals want the arrangement to satisfy their concerns about cost control, market share, outpatient imaging center ownership, clinical quality, patient safety, medical staff satisfaction, competition, regulatory compliance, and utilization control. Priorities shift from one hospital to the next, but these concerns usually float to the top of most lists.

- Acknowledge the concerns of both parties. If physicians trivialize hospital concerns or if the hospital feels physician concerns pale by comparison to their big issues, don’t expect much progress toward a collaborative agreement. Coming together requires each party to take a certain degree of ownership in the other’s problems. “Your” problems become “our” problems in a genuine partnership.

- Calculate performance thresholds and performance requirements necessary to satisfy hospital and physician needs. Using prioritized issue lists, figure out what it will take to satisfy each need. Focus on the top priorities first and be prepared to make increasing concessions as you work your way down the list. You will likely have to adjust demands and expectations when careful analysis reveals unrealistic goals.

- Perform an economic impact analysis of multiple scenarios. Look at a range of options such as productivity-based contracts, joint ventures, and full employment. The options that make sense will depend on the group makeup. Groups with multiple hospital contracts have different concerns than those serving only one hospital. Practices that own and operate freestanding imaging centers bring a whole range of issues of no concern to those who don’t.

- Hammer out the details. Moving from broad principles to concrete contract provisions will prove challenging. But if you spend the time and make the effort to minimize antagonism and get beyond the problems that have dogged you in the past, working out the mechanics will be a little easier. In the acquisition spree of the 1990s, hospitals lost money and felt burned because the productivity of owner physicians dropped significantly once they became employees with guaranteed salaries. That huge hospital concern is being addressed with production-based incentives being a significant component of new employment contracts.

Jethani notes employment arrangements are easier for local, single-hospital radiology groups without an independent imaging center. Determining the disposition of a group’s imaging center can complicate the deal on a colossal scale.

Employment, Really?

In an industry where it has been difficult to work out contract exclusivity in which the radiologists agree not to read for competing hospitals, how can the two sides even broach the subject of employing a group of radiologists? Employment represents the ultimate in exclusivity. The issue, however, isn’t simply exclusivity; it really boils down to risk. An exclusive independent service contract may leave many factors outside the control of the medical group. That intensifies the radiology group’s sense of risk.

An acceptable employment agreement balances risk and reward between the employer and the employee because, in the end, they are one entity. Of course there’s risk in signing an employment agreement—if things don’t turn out well, the radiologist may have to leave the community altogether to continue his or her career. So there is a sense of burning certain bridges when you accept an employment offer.

But if you’ve laid a proper foundation, direct employment is no longer unthinkable. In fact, hospitals and radiologists are doing more than thinking about it. Some hospitals have signed on radiologists, and many more are exploring the possibilities. After doing the hard work of letting go of past difficulties and developing a new level of trust, groups pursuing an employment model still find themselves navigating potential stumbling blocks, including the following:

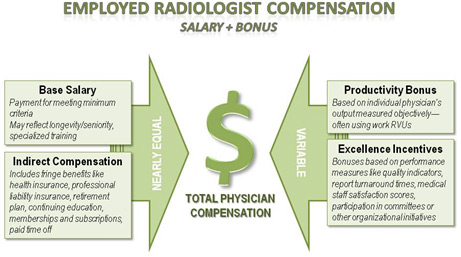

- contract details and performance expectations (see Figure 2 for general components of a typical compensation scheme);

- a sense that everyone is treated fairly in scheduling, productivity measures, working within one’s own specialty, workload, and case distribution; and

- addressing specific concerns such as referring physician collaboration and appropriate assignment of readings to the most qualified physician.

Even nonemployment arrangements fare better under a base-plus-productivity contract. Stampp says that combination provides a sense of stability while fostering a culture that values effort and output. The physicians can focus on important issues such as quality of care and appropriate utilization rather than worrying about the next paycheck.

MIS’ strategy has seen good results from successful relationships they’ve helped craft, both in employment and in independent contractor arrangements. That said, none of the hospitals with which they’ve negotiated employment arrangements agreed to be interviewed for this article; it remains a sensitive topic.

Stampp says one of the keys to success has proven to be the formation of an effective “operating committee.” Each radiologist has input with his or her peers regarding quality control and improvement. The hospitals and radiologists work together to eliminate waste and optimize productivity, resulting in better compensation for the radiologists, better care for patients, and reduced costs and a better bottom line for the hospital. He says a good arrangement strives for transparency, with economic and quality metrics available to all parties. This helps build trust and keeps physicians engaged and incentivized by processes that benefit a hospital’s pursuit of broader organizational goals. In some cases, Stampp says it has yielded results beyond expectations in some arrangements, including the following:

- Radiologists have earned an additional $80,000 per year.

- Hospitals have done away with subsidies.

- Average turnaround times have dropped from 24 hours to six hours in some organizations.

- Referring physician satisfaction surveys show significant improvement (up from 3.8 to 4.5 on a 5-point scale).

Will employment work for every situation? Of course not—one size fits all is still a myth. Healthcare delivery will continue toward tighter integration, and that calls for better collaborative relationships—no matter what finally happens with health reform. But if radiologists and hospital relationships continue to be plagued with mistrust and suspicion, the future looks pretty bleak.

— Timothy W. Boden, CMPE, based in Starkville, Mississippi, has spent 24 years in practice management as an administrator, consultant, journalist, and speaker.

Figure 1

Figure 2