On the Case

On the Case

By Joseph Ryan, MD; Caleb Busch, MD; and Alex Merkulov, MD

Radiology Today

Vol. 24 No. 4 P. 30

History

A 92-year-old woman with a past medical history significant for breast cancer status post-bilateral mastectomy, hypertension, and atrial fibrillation/ flutter status post-ablation and pacemaker placement presented with a three-day history of abdominal pain and cramping. She was seen by her primary care physician and underwent an abdominal X-ray, which raised the possibility of a bowel obstruction. The patient was referred to the emergency department, where she presented with lower suprapubic cramping and pressure. She also reported feeling bloated with her last bowel movement occurring three days prior. She denied nausea, vomiting, fever, and chills. She had no recent colonoscopy or history of abdominal surgery. On physical exam, her abdomen was softly distended and nontender to palpation with hyperactive bowel sounds.

Findings

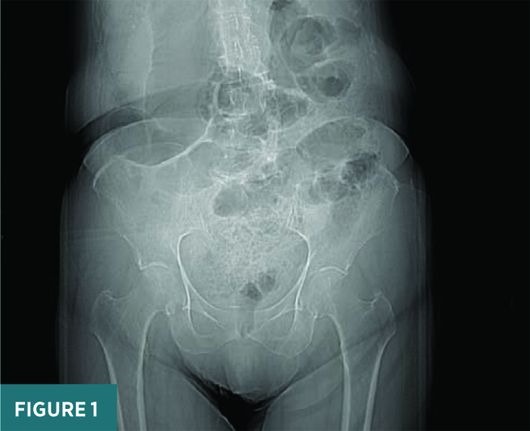

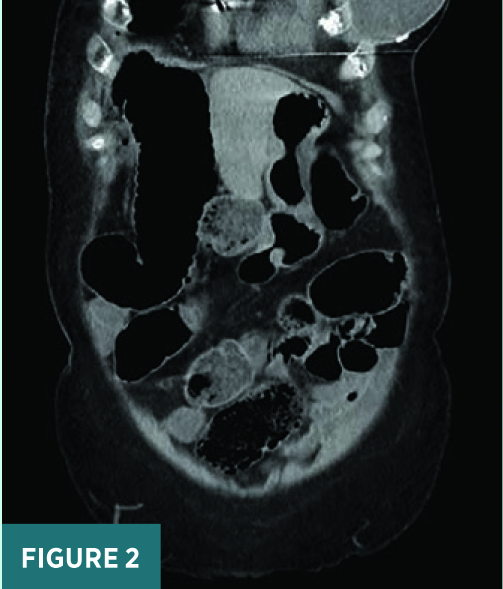

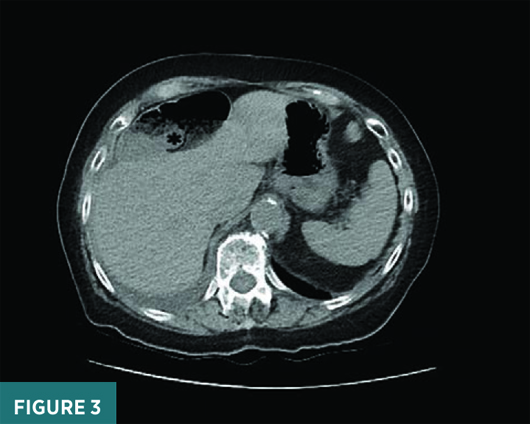

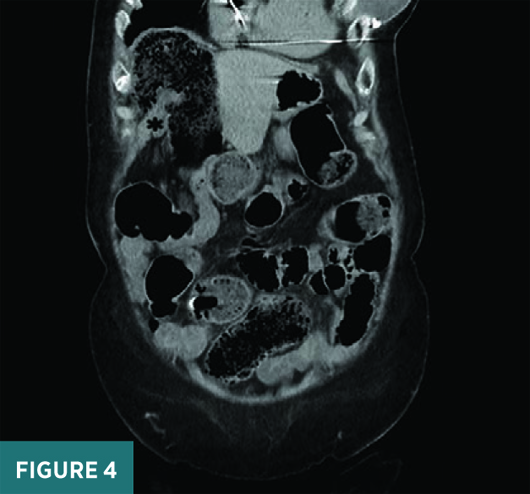

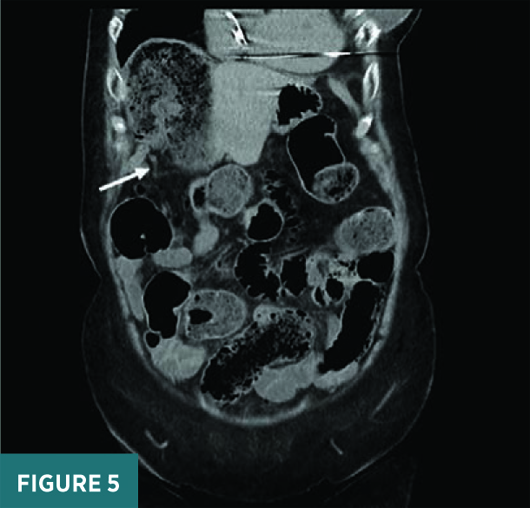

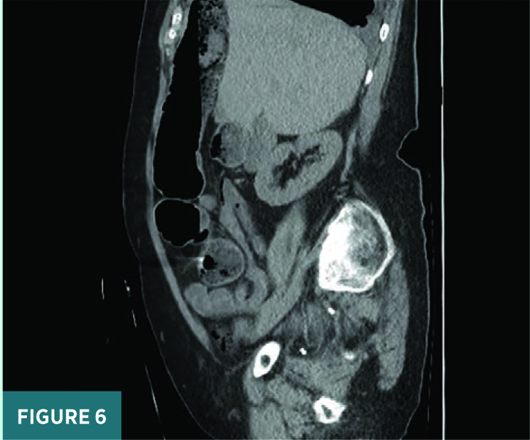

CT scout view (Figure 1) demonstrated a moderately air-distended right upper quadrant “kidney-shaped” portion of the large bowel without bowel wall thickening. On coronal, axial, and sagittal CT images (Figures 2-6), the cecum was folded anteriorly and superiorly without evidence of torsion and situated in the right upper abdominal quadrant anterior to the liver. Visualization of the terminal ilium (black asterisk) and the normal appendix (white arrow) in the right upper quadrant confirmed the diagnosis of a cecal bascule without pericolonic edema, ischemic changes, or perforation. The patient had a significantly redundant colon and a very large colonic stool burden.

After surgical team evaluation, an enema was administered to decompress her stool burden, allowing her to have a bowel movement, and her clinical symptoms subsequently improved. She was discharged from the emergency department with plans for outpatient follow-up at a surgery clinic.

Diagnosis

Cecal bascule, an uncommon form of cecal volvulus

Discussion

Cecal volvulus is an uncommon clinical entity caused by torsion or rotation of a mobile cecum, distal ileum, and/or ascending colon. It usually occurs in individuals who lack functional cecal fixation. The risk of developing a cecal volvulus increases during periods of illness, with 12% to 28% of reported cases occurring in patients hospitalized for other illnesses.

Cecal volvulus accounts for 1% to 3% of all adult intestinal obstructions and is subdivided into three main subtypes: clockwise axial rotation, loop torsion of the cecum with the terminal ileum, and anterior-superior folding without rotation, which is known as a cecal bascule.

Cecal bascule is the least common subtype of cecal volvulus in which the cecum folds upward and anteriorly on the ascending colon without torsion or twisting. This folding can result in a deep crease or fold, which can lead to a mechanical bowel obstruction secondary to a flap-valve mechanism. Compared with other subtypes of cecal volvulus, cecal bascule is less likely to cause vascular compromise. Cecal bascule is mostly encountered in patients with hypermobility of the cecum. It has also been reported that postoperative adhesions may fix the anterior cecal wall to the anterior wall of ascending colon, thereby leading to cecal bascule.

Clinical presentation can be either acute or intermittent; symptoms can include abdominal distension, constipation, nausea and vomiting, and abdominal pain. Mild symptoms tend to occur in elderly patients due to diminished pain sensation. In patients with recurrent or persistent abdominal pain and distension, cecal bascule should be considered.

In cecal volvulus, the classical finding on abdominal radiography is a malpositioned gas-distended cecum with an air-fluid level, with cecal location varying based on volvulus subtype. The associated presence of an air-distended appendix is an extremely helpful finding to suggest and further support the diagnosis. The focally distended, rounded, air-filled cecum may present as a loop with haustral markings resembling a coffee bean. The “coffee bean sign” is more typical of sigmoid volvulus.

On CT imaging, the ectopic location of the distended cecum can be confirmed by running the bowel and identifying the terminal ileum, the ileocecal valve, and the appendix. An associated “whirl sign” is an important finding on CT and may involve swirling bowel loops, mesenteric fat, and engorged ileocecal vessels. The “whirl sign” is diagnostic of volvulus and is typical of the axial torsion and loop subtypes. The bascule subtype is not associated with twisting or torsion, and, therefore, no whirl sign is expected.

Severe potential complications of cecal volvulus include bowel strangulation secondary to torsion of the vascular pedicle compromising blood supply, bowel wall ischemia, and perforation. A cecal diameter greater than 10 cm to 12 cm is considered suspicious for significant disease severity, with associated high risk of perforation.

Nonsurgical treatment of cecal volvulus with endoscopy is limited due to its relative ineffectiveness and associated high recurrence rates and risk of bowel ischemia. Thus, surgery represents the treatment of choice for cecal volvulus, in contradistinction to sigmoid volvulus, which can more successfully be managed using endoscopic detorsion.

At this time, there is no clear consensus on the diagnosis and treatment of cecal bascule. The majority of patients will ultimately require surgical management. Surgical management options with viable bowel include detorsion and fixation with cecopexy or hemicolectomy. Studies have shown increased risk of recurrence with cecopexy so some advocate for hemicolectomy as a more definitive treatment option. Alternatively, hemicolectomy is comparatively associated with increased mortality. Ultimately, the choice of management strategy should be based on patient risk stratification, viability of the involved bowel segment, and operator experience, as well as incorporating a shared decision-making model with patient informed consent.

Joseph Ryan, MD, is a radiology resident at UConn Health at the University of Connecticut in Farmington.

Caleb Busch, MD, is a radiology resident at UConn Health.

Alex Merkulov, MD, is an associate professor of radiology at UConn Health.