On the Case

On the Case

By Shabaz Khan, BA; Karen Makhoul, BS; and Anna Luisa Kuhn, MD, PhD

Radiology Today

Vol. 26 No. 5 P. 30

History

A 71-year-old female with a past medical history of osteoarthritis, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, depression, and macular degeneration presented with hip pain following a mechanical fall at work. The patient landed on her right hip and struck the left side of her head, but did not lose consciousness. CT of the head and pelvis were obtained as part of the trauma workup.

Findings

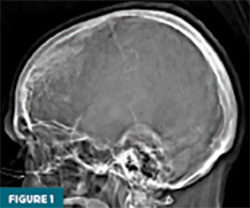

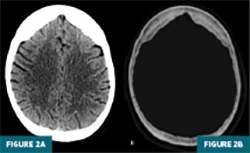

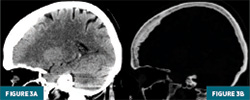

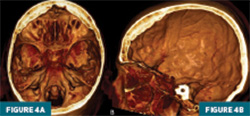

A CT localizer radiograph suggested osseous overgrowth along the frontal bone (Figure 1). Axial CT head images at the level of the frontal lobes confirmed thickening of the frontal bone on soft tissue window (Figure 2A) and bone window (Figure 2B). Sagittal CT head reconstructions at the level of the basal ganglia redemonstrated the thickening along the inner surface of the frontal bone on soft tissue window (Figure 3A) and bone window (Figure 3B). 3D reconstructions of the skull in axial (Figure 4A) and sagittal (Figure 4B) planes demonstrated the normal appearance of the outer table, diploe. and inner table, with benign osseous overgrowth extending from the inner table of the frontal bone.

Diagnosis

Hyperostosis frontalis interna (HFI)

Discussion

HFI is a benign, idiopathic thickening of the inner surface of the frontal bone, typically discovered incidentally on neuroimaging.1 It is usually bilaterally symmetrical and may extend to involve the parietal bones. It was first described in 1719 by Morgagni as a pathology accompanying hirsutism and obesity and later recognized as an independent pathology by Caughey in 1958.1 HFI is morphologically classified into four different categories (A, B, C, D) based on the calvarium and extent of bone overgrowth, with type D being the most advanced form.2 Increased vascularization and osteogenesis are observed on the dural side of the inner cortical layer, which suggests that HFI may result from diploization within the inner table due to ongoing bone remodeling.3 Though often dismissed as clinically insignificant, its growing recognition in aging populations, particularly postmenopausal women, warrants further attention from clinicians, especially in trauma and geriatric care settings.1

HFI has a marked prevalence in females, particularly manifesting in postmenopausal women.1,4 Its pathogenesis remains unclear, though endocrine and hormonal theories, such as the role of estrogen, are frequently proposed.1,5 Estrogen’s potential involvement is based on its influence on bone metabolism, where a decreased level is associated with an increase in bone turnover (osteoclast activity) and potential abnormal calcification in the frontal bone.6 Cases of HFI in males are associated with decreased androgen stimulation or suppression from treatment (eg, hormone-related treatment for prostate cancer) or conditions associated with hypogonadism (eg, Klinefelter’s syndrome and testicular atrophy).5

Additional hypotheses suggest links to obesity and metabolic syndromes. 7 HFI can also occur as part of a broader condition known as Morgagni-Stewart-Morel syndrome, which includes a combination of HFI, metabolic abnormalities (eg, obesity and diabetes), endocrine disorders (eg, thyroid dysfunction, hirsutism), and neuropsychiatric symptoms such as depression or cognitive impairment.8

HFI can be mistaken for other bone pathologies such as Paget’s disease, fibrous dysplasia, osteoma, and malignancy. 9 Unlike HFI, Paget’s disease is characterized by an elevated alkaline phosphate level and abnormal bone remodeling, often resulting in enlarged and deformed bones, which can cause pain or fractures.10 Fibrous dysplasia, a condition characterized by replacement of normal cortical bone by immature fibro-osseous tissue intermixed with woven bone, frequently affects craniofacial bones and presents during adolescence as painless swelling or facial asymmetry.11 In contrast, osteomas are benign dense sclerotic bone that typically present asymptomatically or with headaches.11 Malignancy, particularly metastatic disease, may present as irregular bone lesions or cortical destruction, but usually with other systemic signs such as weight loss or pain specific to the involved region.12 Recognizing HFI’s distinct features without significant clinical symptoms helps avoid unnecessary testing or misdiagnosis.

Treatment for HFI is typically reassurance and clinical observation, as the condition is asymptomatic in most cases.13 In rare instances where HFI is associated with symptoms—such as headache, cognitive changes, or features of Morgagni-Stewart-Morel syndrome—treatment is directed at the associated condition rather than the bony overgrowth itself.8 However, surgical decompression can also be done to alleviate symptoms.13

In conclusion, HFI is often incidental and benign but holds increasing clinical relevance, particularly in postmenopausal women. Its etiology is thought to involve metabolic syndromes and hormonal factors, with estrogen exposure playing a key role. While HFI itself typically requires no treatment, clinical familiarity allows providers to distinguish it from pathologic conditions, avoid unnecessary workup, and offer appropriate reassurance based on imaging and clinical context.

Shabaz Khan, BA, is a medical student at the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School in Worcester.

Karen Makhoul, BS, is a medical student at the University of Massachusetts Chan Medical School.

Anna Luisa Kuhn, MD, PhD, is an associate professor in the division of neurointerventional radiology in the department of radiology at the University of Massachusetts Medical Center.

References

1. Raikos A, Paraskevas GK, Yusuf F, et al. Etiopathogenesis of hyperostosis frontalis interna: a mystery still. Ann Anat. 2011;20;193(5):453-8. Epub 2011 May 27. PMID: 21684729.

2. Hershkovitz I, Greenwald C, Rothschild BM, et al. Hyperostosis frontalis interna: an anthropological perspective. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1999;109(3):303-25.

3 Morita K, Nagai A, Naitoh M, Tagami A, Ikeda Y. A rare case of hyperostosis frontalis interna in an 86-year-old Japanese female cadaver. Anat Sci Int. 2021;96(2):315-318.

4. Western AG, Bekvalac JJ. Hyperostosis frontalis interna in female historic skeletal populations: Age, sex hormones and the impact of industrialization. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2017;162(3):501-515.

5. Cvetković D, Nikolić S, Brković V, Živković V. Hyperostosis frontalis interna as an age-related phenomenon - Differences between males and females and possible use in identification. Sci Justice. 2019;59(2):172-176.

6. Fischer V, Haffner-Luntzer M. Interaction between bone and immune cells: Implications for postmenopausal osteoporosis. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2022;123:14-21.

7. Verdy M, Guimond J, Fauteux P, Aube M. Prevalence of hyperostosis frontalis interna in relation to body weight. Am J Clin Nutr. 1978;31(11):2002-4.

8. Attanasio F, Granziera S, Giantin V, Manzato E. Full penetrance of Morgagni-Stewart-Morel syndrome in a 75-year-old woman: case report and review of the literature. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2013;98(2):453-457. https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2012-3242

9. She R, Szakacs J. Hyperostosis frontalis interna: case report and review of literature. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 2004;34(2):206-208.

10. Kravets I. Paget's Disease of bone: diagnosis and treatment. Am J Med. 2018;131(11):1298-1303.

11. Wilson M, Snyderman C. Fibro-osseous lesions of the skull base in the pediatric population. J Neurol Surg B Skull Base. 2018;79(1):31-36.

12. Greenberg HS, Deck MD, Vikram B, Chu FC, Posner JB. Metastasis to the base of the skull: clinical findings in 43 patients. Neurology. 1981;31(5):530-537.

13. Li Y, Wang X, Li Y. Hyperostosis frontalis interna in a child with severe traumatic brain injury. Child Neurology Open. 2017;4:2329048X17700556.