On the Case

On the Case

By Joseph Ryan, MD, and Alex Merkulov, MD

Radiology Today

Vol. 25 No. 2 P. 30

History

A 44-year-old woman in her normal state of health presented for a baseline screening mammogram. The patient had no breast-related clinical concerns but did report a personal history of asthma and pulmonary fibrosis secondary to smoking.

Findings

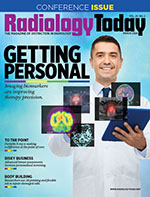

Bilateral full field digital tomosynthesis 3D with synthesized 2D mammography using standard craniocaudal and mediolateral oblique (MLO) projections did not demonstrate evidence of malignancy in either breast. The right breast was significantly smaller in reference to the left breast, with associated hypoplasia of the right pectoralis muscle on the MLO projection (Figure 1). The breast parenchyma was heterogeneously dense. There was no axillary lymphadenopathy.

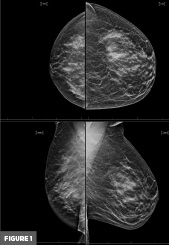

No prior breast imaging was available for comparison; however, a prior chest radiograph, which was performed seven months earlier, also demonstrated asymmetric underdevelopment of the right breast (Figure 2).

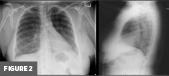

Additionally, a CT of the chest performed 10 years earlier demonstrated underdevelopment of the upper anterior right hemithorax with significant hypoplasia of the right pectoralis major, right pectoralis minor aplasia, and asymmetrically diminutive right breast (Figure 3).

Additional prior outside imaging reports were available in the patient’s chart, though the actual images were not available for direct comparison. No prior imaging study mentioned the above-described congenital anomalous findings involving the right hemithorax. Also of note, the patient had a prior outside nuclear medicine ventilation-perfusion scan that described “mild diffusely decreased perfusion to the left lung without a segmental defect,” with suggestion of possible underlying chronic pulmonary embolism or Swyer-James syndrome, with recommendation for further evaluation with CT imaging.

Diagnosis

Poland syndrome

Discussion

Poland syndrome is a rare congenital syndrome with an estimated incidence of approximately 1 in 30,000 live births. It is characterized by unilateral thoracic hypoplasia with underdevelopment or absence of chest wall musculature as well as ipsilateral limb abnormalities in some cases, such as syndactyly or brachydactyly, in addition to underlying malformations of the subjacent rib cage, upper extremity long bones, breasts, axilla, and, in some cases, the kidneys. Either side of the body can be affected, although the right hemithorax is most often involved, as was the case in this patient, comprising approximately 75% of reported cases. 3:1 male-to-female predilection is reported. Poland syndrome may also occur concurrently with other underlying developmental anomalies.

First identified in 1841 during an autopsy performed by then medical student Sir Alfred Poland, this interesting condition was subsequently described and later named after Poland for his discovery. This first documented case specifically described agenesis of the pectoralis major (most notably the sternocostal head), pectoralis minor, and other associated muscular deficiencies, as well as ipsilateral hand brachysyndactyly.

The precise cause of Poland syndrome remains unknown. However, proposed etiologies include disruption of the blood supply to developing embryonic tissue precursors to the chest wall and upper extremity structures, causing ischemia and stunted development of these structures in utero. Vascular involvement of the subclavian artery may be the most likely culprit, given its location and distribution of perfusion. Familial cases have also been documented, raising suspicion for possible underlying hereditary and/or genetic predispositions.

Phenotypic levels of expression can also vary widely. Historically, no specific guidelines for diagnosis, classification, and management of patients were available; however, recent efforts have been made to establish such criteria. Classification systems based on degree of underdevelopment have recently been proposed. Additionally, methods of standard arising from imaging and clinical investigations, clinical severity scoring parameters, and treatment algorithms continue to be explored.

In some cases, patients may benefit from and desire plastic surgery in order to surgically construct the underdeveloped chest wall and/or breast primarily focused on cosmetic results. Studies reported in the literature have specifically focused on psychological measures such as body self-perception following breast reconstruction in females affected by Poland syndrome, with results showing improved quality of life. Additionally, some improvement in function and mobility may be seen, especially when combined with physical therapy. Pediatric patients diagnosed early with this condition can benefit from more conservative methods that aim to modify the shape of the thoracic cage, which can be done more easily in skeletally immature patients due to having more malleable ribs and flexible sternal attachments. Such treatments include use of the vacuum bowel to address pectus excavatum deformity and corsets to treat pectus carinatum deformity. Some more technologically advanced treatment options under investigation include 3D-printed, custom- made rib prostheses.

Utilization of a stepwise treatment approach spread over time and multidisciplinary team involvement are highly encouraged. Early diagnosis is perhaps the most important factor to ensure optimal outcomes. In some cases, Poland syndrome can even be diagnosed prenatally, especially when associated with additional underlying congenital anomalies. However, significantly delayed diagnosis well into adulthood is a common occurrence, especially when patients are otherwise asymptomatic.

Unfortunately, lack of recognition and tailoring of management for patients with this condition remains quite common. Indeed, this appears to have been the case with this patient, with no mention of Poland syndrome throughout the patient’s medical chart despite it being present in multiple prior imaging studies. Although the direct consequences of this condition appear to be noncontributory to the patient’s daily life, there were several instances where the presence of this condition may have indirectly had implications for her medical care.

Breast cancer screening, for example, can present technical challenges related to the underdeveloped chest wall as well as breast hypoplasia. Despite a variable asymmetrically decreased or absent breast tissue on the affected side, female patients with this syndrome are still at risk of breast cancer and should be followed up using standard established screening protocols. Additionally, evidence from the literature suggests that patients with Poland syndrome can have an increased risk of malignancy on the affected side.

Poland syndrome may have other less obvious indirect implications for patient management, as was potentially the case with a prior outside nuclear medicine ventilation/ perfusion (VQ) scan eight years prior, which described asymmetric diffusely decreased perfusion throughout the left lung without a segmental defect. The exact cause of this finding was never specifically addressed in subsequent documentation throughout the patient’s chart. While this finding can occur secondary to various underlying etiologies, one possibility that should have been considered is the asymmetrically increased amount of tissue overlying the left chest wall relative to the hypoplastic right chest wall. It is likely that knowledge of this patient’s underlying Poland syndrome would have influenced the interpretation of this VQ scan, with potential implications for subsequent recommendations and patient management.

Consensus-based recommendations for the diagnosis and medical management of Poland syndrome have recently been published.1 However, awareness and familiarity of this rare syndrome continue to hinder care for afflicted patients. Thus, educating providers about this unique syndrome is an important precursor step to ensuring the earliest possible diagnosis and establishing optimal treatment to achieve the best outcomes possible.

— Joseph Ryan, MD, is a radiology resident at UConn Health at the University of Connecticut in Farmington.

— Alex Merkulov, MD, is an associate professor of radiology at UConn Health at the University of Connecticut.

References

1. Baldelli I, Baccarani A, Barone C, et al. Consensus based recommendations for diagnosis and medical management of Poland syndrome (sequence). Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2020;15(1):201.

Resources

1. Frioui S, Khachnaoui F. Poland's syndrome. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;21(1):294.

2. Iyer RS, Parisi MT. Multimodality imaging of Poland syndrome with dextrocardia and limb anomalies. Clin Nucl Med. 2012;37(8):815-816.

3. Sparks DS, Adams BM, Wagels M. Poland's syndrome : an alternative to the “vascular hypothesis.” Surg Radiol Anat. 2015;37(6):701-702.

4. Stylianos K, Constantinos P, Alexandros T, et al. Muscle abnormalities of the chest in Poland's syndrome: variations and proposal for a classification. Surg Radiol Anat. 2012;34(1):57-63.

5. Chowdhury MK, Chakrabortty R, Gope S. Poland's syndrome: a case report and review of literature. J Pak Med Assoc. 2015;65(1):87-89.