By Ashok Madan, MD, PhD, and Robert Saul, MD

History

A 72-year-old white man with a past medical history of well-controlled hypertension, hyperlipidemia, corneal transplant, and renal stones presented to an ophthalmology clinic for a routine visit. The patient’s granddaughter and wife had noticed inward rotation of the left eyeball. He complained of mild sinus pressure but wasn’t experiencing headache, nausea, or vomiting. The clinical exam showed horizontal uncrossed diplopia that worsened in left gaze, with abduction of the left eye globe consistent with left cranial nerve VI palsy. There was no nystagmus, proptosis, enopthalmos, or cranial nerve III or IV palsy. There also was no ptosis with symmetric pupillary responses.

Findings

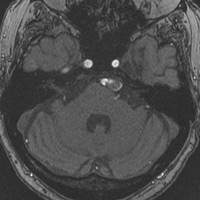

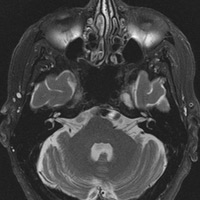

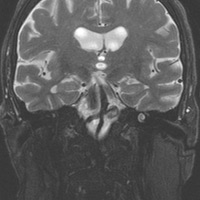

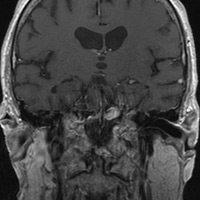

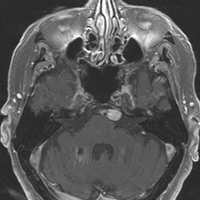

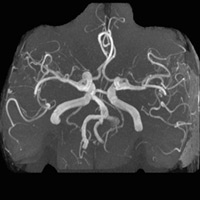

MR of the brain revealed an ovoid 1-cm saccular aneurysm on the left at the vertebrobasilar junction that impressed on the ventral left pons at the root entry zone of the left abducens nerve (Figures A, B, and C). The aneurysm extended along the expected cisternal course of left cranial nerve VI, diffusely enhancing on postcontrast T1 images (Figures D and E). MR angiogram concomitantly depicted the aneurysm with intraluminal flow artifact (Figure F).

Diagnosis

A 1-cm basilar artery aneurysm contributing to isolated left abducens nerve palsy

Discussion

Acute isolated abducens nerve palsy is a common neuro-opthalmic problem encountered by general ophthalmologists. Its etiology remains undetermined in 25% of cases despite exhaustive diagnostic evaluation. The majority of cases of cerebral nerve VI palsy are microvascular ischemic nerve injury due to diabetes or hypertension with spontaneous improvement over several months. Abducens nerve is susceptible to injury along its course from its root entry zone at the ventral pontomedullary junction to the cisternal portion within the subarachnoid space, within Dorello’s canal, cavernous sinus, and superior orbital fissure to its final destination in the ipsilateral lateral rectus muscle.

Aneurysms in the vertebrobasilar circulation are rare, comprising only 15% of all intracranial aneurysms. Nearly 80% of posterior circulation aneurysms arise from the basilar artery. The majority are basilar tip aneurysms at or near its termination. Vertebrobasilar junction aneurysms account for only 3% to 4% of posterior circulation aneurysms. Giant vertebrobasilar junction aneurysms, those exceeding 2.5 cm in their greatest dimension, are even more rare and mostly saccular in morphology.

Approximately 50% of patients suffer from spontaneous rupture of these giant aneurysms, with mortality greater than 60% within two years. Unruptured aneurysms may have an insidious onset usually related to mass effect. Symptoms related to aneurysm location may include visual disturbances, cranial nerve palsy, and seizures.

The majority of aneurysms are amenable to neurosurgical or interventional neuroradiological management. Endovascular management of large/giant posterior circulation aneurysms is a formidable challenge and associated with a significantly greater proportion of worse clinical outcome. The mode of treatment is based on the aneurysm size, geometry, location, morphology, and hemodynamics.

— Ashok Madan, MD, PhD, and Robert Saul, MD, are staff neurologists at the Salem VA Medical Center in Virginia.

|

|

| Figure A | Figure B |

|

|

| Figure C | Figure D |

|

|

| Figure E | Figure F |

Resources

- Choi IS, David C. Giant intracranial aneurysms: development, clinical presentation and treatment. Eur J Radiol. 2003;46(3):178-194.

- Limaye US, Baheti A, Saraf R, Shrivastava M. Endovascular management of giant intracranial aneurysms of the posterior circulation. Neurol India. 2012;60(6):597-603.

- Chi SL, Bhatti MT. The diagnostic dilemma of neuro-imaging in acute isolated sixth nerve palsy. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2009;20(6):423-429.

- Rush JA, Younge BR. Paralysis of cranial nerve III, IV and VI. Cause and prognosis in 1,000 cases. Arch Ophthalmol. 1981;99(1):76-79.

- Suri A, Mehta VS. Giant vertebrobasilar junction aneurysms: unusual cases. Neurol India. 2003;51(1):84-86.

Submission Instructions

- Cases should have clinical relevance and clear radiological findings.

- Seconds should include a title, history and course of illness, findings, diagnosis, and discussion.

- Word count should not exceed 800. At least three references are recommended.

- Cases may be submitted from any radiological subspecialty and imaging modality.

- Figures must be high-quality JPEG or TIFF images and labeled for ease of reference. Please keep images in their native format, without the addition of arrows or other means of highlighting the key findings.

Submit cases via e-mail to Rahul V. Pawar, MD, at rvp325@gmail.com or to Radiology Today at jknaub@gvpub.com.

Department of Radiology, Division of Neuroradiology

Saint Barnabas Medical Center/Barnabas Ambulatory Care Center